One of the least known bubbles in financial history was railway mania which occurred in Britain between the 1830s through the 1850s. After the Bubble Act of 1720 was repealed in 1825, investor’s appetites for speculating in the train industry started to gain steam. Investor euphoria produced a bubble only in British railway stocks and not in any other industry. The 1840s marked a dramatic change for British accountants. There was a rising demand for accountants during the period of railway mania. The rise in demand for accountants outside the railway enterprise was to ensure an independent analysis of the company’s finances. William Deloitte set up his own practice in London in 1845 which would eventually to grow to one of the largest accounting firms in the world. Several important factors that still have relevance in financial markets today emerged during the railway bubble including overbuilding caused by low interest rates, corporate wrongdoing, financial statement fraud, and the emergence of the first “bearish” investor. A bearish investor is an individual who believes market prices are too high and should be lower as per a specific set of analyses.

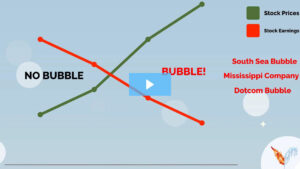

The price bubble that formed in railway stocks in the 1830s throughout the 1850s was attributed to one of the most widely-analyzed pieces of a company’s internals, the financial statement. Academic studies point to accounting fraud, such as paying dividends out of shareholder capital, as one of the motivating reasons that caused investors to bid up the prices of railway stocks past realistic values. Victorian investors valued shares based primarily on its dividend yield. Investors would keep up with weekly periodicals to stay vigilant of the direction of a company’s dividend. The “Railway King” George Hudson is frequently cited as the most prominent fraudsters having misappropriated shareholder money for his own benefit. More extreme views of accounting fraud have emerged such as corporate managers deliberately overstating earnings to cause an increase in the share price, in which to sell their stock at higher prices and understating earnings to drop the stock price to buy back in.

Robert Lucas Nash was a financial analyst that pulled the veil back on the accounting fraud that occurred across popular railway stocks. Nash was the first bearish investor that did not believe in the rosy expectations the railway industry was projecting. By early 1848, Nash wrote about “honest” vs “dishonest” dividends and published his analysis taken from publicly available data into a popular railway periodical called the London Weekly Railway Share List (LWRSL). Nash pointed out that there is a general impression across investors that the dividends paid by railway companies were not from actual profits. He went into detail about the improper accounting such as including replacements of locomotives to being charged to capital, and some costs of main lines being improperly allocated to branches under construction, allowing profits to be multiplied across a smaller asset base thus inflating profit margins. It became apparent that train revenues were increasing year-over-year, but revenue per miles was not. The price of the shares did not justify the company’s dividend payment and it became evident dividends were not being paid from profit, but rather from shareholder capital. Railway investors began using his analysis at shareholder meetings. Shareholders questioned corporate managers about the accounting that was taking place. This caused corporate managers, railway enthusiasts, and the large railway publications to grow distasteful of Nash’s analysis. Nash was banned from writing for the LWRSL but went on to start his own weekly periodicals, the Money Market Examiner and Railway Review, where despite the name, wrote extensively about the skepticism in railway financial reporting. Nash’s analysis would end up being correct as the railway mania came to a crashing halt in 1849.

The Bank of England cut interest rates low enough to create a massive upsurge in the building of railroads. Investments in building railways increased rapidly. However, low interest rates caused the supply of railroad tracks to increase faster than the demand for railway services. Original financial projections of the railway sector’s potential trajectory were vastly overoptimistic and as a result, investors pushed railway stock prices to levels that did not line up with the company’s true profit potential. Investors thought they were obtaining a clear and rosy picture of the company’s health via its financial statement and began buying shares of railway stocks using borrowed funds, or leverage. Investors could own railway stocks for only 10% of the stock price at the time when the company was formed. Investors had the obligation of receiving “calls” from company management for the remainder of the funds. Many hoped to buy shares with a small deposit in hopes of reselling them for a profit quickly without having to deposit the remaining funds. However, investors began to sell in a mad rush when railway share prices began falling in the late 1840s. Many railway investors had to meet their calls during the slide in share prices.

The period during railway mania saw the emergence of financial statement fraud perpetrated by corporate managers but most certainly would not be the last. Carefully crafted disinformation by individuals at the time such as Wyndham Harding kept investors reassured that they were only facing temporary setbacks as a railway stock prices began to trade up and down violently. The suppression of statistics between the years of 1842-1847 concealed the grim reality. The emergence of the financial statement created a new supply of information regarding different branches of rail lines, the lengths, costs, and expenses associated with each as well as multiple classes of shares. The vast amount of information regarding railway stocks was available to the public for the first time but different methods of accounting treatments increased the possibility for financial statement fraud. Railway mania would not be the only bubble episode to have been inflated because of accounting fraud and excess leverage. Choo! Choo! Volatility is on its way.