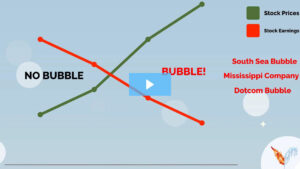

Another major stock bubble was forming in Britain at the same time during the formation of John Law’s Mississippi Company bubble. Britain’s economy was in financial ruin after the War of the Spanish Succession between 1701 and 1714. Internal audits of Britain’s finances showed the country was 9 million pounds in debt. The potential for the British government to pay back their debts was so low that the government’s bonds were priced at 50% discount of their face value. In 1711, a plan was drawn up by a private organization to take over and manage the country’s growing debt. A board of directors were put in charge of a company they named “The South Sea Company.” The company would have a government-funded trading monopoly; specifically with the Spanish colonies in the South America, a zone known as the South Sea. Holders of British debt could exchange their certificates for shares in the South Sea Company and Britain would make interest payments to those investors. The South Sea had two revenue streams: a stream of cash from the British government and trading profits that would hopefully flow from South America.

The arrangement of the South Sea Company was peculiar as Britain was somehow supposed to make profits from the very country it was at war with. Nevertheless, investors bid up the stock and the hostility between Britain and Spain was put to rest with the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, which ended the war. Just as those who invested in John Law’s Mississippi Company, it was once again believed the gold and silver in South America were to be simply handed over by the natives to the European investors in the South Sea Company. However, it would be seven years until a ship actually set sail to South America. The British government was not making its interest payments to the South Sea Company to pay its shareholders either. In return, the issuance of more shares of stock in the amount of the missed interest payment was offered to shareholders as a way of compensation, diluting the initial shareholder’s investment. One of the first forms of “front-running” occurred during the South Sea bubble as the Lord High Treasurer who knew purchases of government debt would occur by the company rushed out into the open market to buy the deeply discounted bonds at a 45% discount as he knew they would soon be retired at 100% of their face value, resulting in an immediate gain of 55%.

The appeal of the South Sea Company was its potentially lucrative trade route that was to be established with the Spanish colonies in Latin America. However, the fundamentals of the trade agreement were not strong. The hostility between the two countries extended beyond war as the terms with the Spanish king and South Sea Company were disadvantageous to Britain. The terms of the contract were that 25% of Britain’s trade profits plus 5% of its balance would be submitted directly to the king of Spain. The deal was only profitable for the Spanish government. War between Spain and Britain broke out again and the few assets that were held in South America by the South Sea Company were seized by Spain, causing a loss of 300,000 pounds to the company. At this point, the company was nothing more than a small office building in England with a massive amount of unpaid government debt. Nevertheless, rumors of John Law’s success in France swirled throughout London and the amount of new companies that went public alongside the South Sea Company grew. The public was intrigued in investing into companies with much harder to understand business models and unsure prospects. Most businesses pledged to seek gold in the New World but some of the newer companies were committed to outrageous schemes such as trading in hair, selling horse insurance, and even a slogan that read “carrying on an undertaking of great advantage but nobody to know what it is.”

Directors of the South Sea Company were not pleased to see investors shuttling their money into other companies and sought to have the British Parliament pass the Bubble Act of 1720. As requested, the act was passed in June of 1720 which required all publicly traded companies to receive a royal charter. Without a charter, companies were immediately broken up and as a result, dozens of companies were dismantled. The mini stock bubbles that had formed instantly popped as share prices crashed to zero leaving investors penniless. The South Sea Company already had its royal charter its shares shot up to 1,050, a 10-fold increase from six months before. Legislation caused one bubble to pop and an existing bubble to grow even larger. Sir Isaac Newton was caught up in the bubble euphoria. In early 1720, he purchased shares of the South Sea Company. He sold for a profit of 7,000 pounds after the stock price soared from 150 to his selling price of 350. He was saddened to see his friends continue to ride the stock higher to 600, then 700 and 800. Newton could no longer feel the fear of missing out so he tried to make up for lost profit by buying as many shares as he could. He even borrowed funds to purchase more shares of the South Sea Company. Newton was briefly excited to see the stock price vault above 1,000 only to be immediately saddened when the stock crashed below 200 in the second half of 1720, resulting in a 20,000 pound loss.

As the stock price started to fall from its four-digit price, investors became nervous and started to sell their shares as they borrowed funds to purchase the stock and were getting further hesitant about owning shares of stock that was losing its value. Banks and goldsmiths who made loans based on South Sea shares as collateral found themselves at total loss, or otherwise holding the proverbial “bag,” as thousands of investors lost money when the stock price tanked. Parliament was called in for an emergency session in December 1720 to find the root cause of the debacle. Directors of the South Sea Company were deemed the culprits as political corruption, bribes, and widespread fraud reached all levels of government. Heavy fines and prison sentences were given out to the directors who had not yet fled Britain already. Their estates were confiscated to raise a payback fund for those who lost money in the scheme. Sir Robert Walpole was put in charge to clean up the aftermath of the South Sea bubble as the British economy was in worse shape than before. It took an entire century for Britain to recover and the issuance of shares became outlawed only to be repealed more than one hundred years later in 1825. The repeal of the act would eventually give rise to the start of Railway Mania in the 1840s. The Bubble Act of 1720 tried to stifle volatility during the South Sea episode only to inflate the bubble further until fear ultimately popped it.