The most roaring part of the 1920s was the consumer’s newly found love for credit and affordable technologies. After World War I ended in late 1918, the middle class enjoyed steadily growing wages as a result from rising labor demand and increasingly affordable goods. The 1920s was the first decade in US history where everyday consumer goods and the “leisure” lifestyle became available to those that were not wealthy. Items such as radios, televisions, canned food, refrigerators, movies, cars, and washing machines became affordable for the American consumer via debt. 90% of furniture, 75% of cars, and 65% of vacuum cleaners were purchased on credit. The way in which items were purchased also changed dramatically during the 1920s as consumers could no longer negotiate on a price as they could prior to the 1920s. A “one-price” policy was implemented by retail stores which made business transactions more efficient and boosted overall revenues. Before the 1920s, a grocery shopper would hand a runner their item list to bring their groceries. After the war, the concept of “self-service” began to emerge as shoppers would now be able to roam the stores freely and gather items at their own pace. Grocery stores enjoyed higher revenues from increased sales and lowered costs for not having to hire runners. The invention of the car induced citizens to sprawl beyond the cities and into the suburbs. Department stores such as Sears opened eight retail stores in 1925 and by 1929, grew to 324. Jobs in road construction, home construction, and electrical services were in high demand. When the federal income tax system was enacted in 1913, rates started at 1% for those making $4,000 and a max of 7% for those making $1 million per year or more. Tax rates reached 77% by 1918 until getting slashed to 24% for the highest income earners. Despite this tax cut, the government revenue increased due to increased spending across income levels. The United States also generated a surplus every of the 1920s, which was used to pay down the modest debt of the country. However, the self-reflexive cycle of greed and fear would run its normal course as the boom that would occur in Florida real estate and eventually the stock market would come to a crashing halt.

The invention of the car spurred the desire for moving out of the city. Florida was perceived a paradise that caused suburbanites to move to the state in large quantities. Between 1920 and 1925, the population of the state grew 30%, from 968,470 to 1,263,540. The main reason for the rush to Florida was to acquire property that was believed to be a good investment. The euphoria in Florida real estate picked up in 1922 when the Miami Herald became the heaviest weighted paper due to the amount of advertisements for land being sold. Stories and headlines pointing out quick and easy profits being earned by those simply willing to take the risk found their way to the mainstream. Cities and towns issued bonds at high interest to businesses flocking to the state. Florida eliminated the state income tax, inheritance taxes, and took on a pro-business attitude to keep up with the growing optimism. Realtors outsourced the task of signing up potentially prospects to “binder boys” who were either young men or women who would stand at any piece of land ready to take an initial deposit. The “binder” was an option contract that allowed the speculator to secure a parcel of land for a fraction of the purchase price, with the obligation of having to deposit the rest of the funds 30 days later. The speculator hoped to sell the binder for a profit before the 30 days.

Disaster began to erode the speculative real estate euphoria by 1925. After a few years of rising land prices, values started to reach ridiculous levels. Real estate prices formed a bubble as a piece of property bought for $1,700 in the early part of the boom reached $300,000 in value, almost 175 times the purchase price. By early 1925, Forbes published a highly skeptical article about the real estate frenzy. At the same time railroads such as Air Line Railroad, Florida East Coast Railway, and Atlantic Coast Railroad began to grow wary of the bottlenecks and headaches that would begin to arise from having to transport goods to Florida. Starting in October 1925, the railway companies stopped shipping building materials and only began shipping food, fuel, and perishables to Florida. In addition to the trade embargo, a 241-foot boat called PrinzValdemar, sank in the mouth of the Miami harbor blocking access to one of the ports where vendors would unload their cargo. Later that same year, a hurricane with 125-mile per hour winds hit South Florida causing so much destruction that would take decades to repair resulting in a crash in real estate prices. However, the decade of great speculation was not over yet as investors hopped over to the stock market in search of the next, best investment.

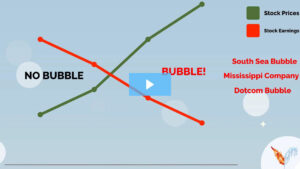

Companies such as Radio Corporation of America, Montgomery Ward, Cities Service all saw their share prices increase rapidly during the 1920s. The stock market rallied in three separate phases. The first phase lasting from August 24, 1921 through October 21, 1926 boosted the Dow Jones by 60%, representing an annual gain of 10%. The next phase saw an acceleration in those values. This stage added another 50 percent to the Dow Jones between October 1926 and June 1928, representing an annual gain of 20%. The third stage was just over a year in length, between June 1928 and August 1929, in which the Dow Jones surged about 90%, meaning annual gains were approaching triple digits, almost an increase in 9 times compared to the first phase. Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover claimed the country was experiencing an “orgy of mad speculation.” What fueled the mania in the stock market was a combination of low interest rates put in place by the Federal Reserve and commercial banks making loans to stock speculation versus business investment. One source of margin or leverage were “call loans” from brokers that allowed customers to buy stocks with as little as 10% of the purchase price. The fever was so great that major corporations such as Standard Oil was loaning out $69 million a day in call loans at the peak of its lending. In 1929, the increase in stock prices was greatly attributed to “stock pools” in which a small group of individuals agreed to bid up the price of a particular stock. The group began to buy the stock in small quantities until the purchased quantity hit the target amount. Once the stock pool met the target quantity, members within the pool began buying and selling the stock to each other while gathering attention from the general public. The speculative public observed the increasing volume and price, assumed something positive happened under the hood, and joined in the bidding. The rising price fed off itself until it reached a massive spike. The members of the stock pool began dumping their shares on the unsuspecting public that were far out of alignment with economic reality. Once the Dow Jones price began to surpass its underlying companies’ corporate profits, a bubble had formed and therefore only had one final fate. Many respected scholars at the time including Professor Irving Fisher from Yale University asserted “stock prices are not high, and Wall Street will not experience anything in the nature of a crash.”

The economy would feel its first economic shock in early 1929 as President Herbert Hoover would sign into law the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, putting a tax on 20,000 different goods. Economists now believe this tariff was ruinous to the economy as retaliatory tariffs by U.S. trading partners were put in place in the early 1930s resulting in a trade war and higher prices to consumers. Greed turned into fear as the market started to slide in September of 1929. Between the peak of September 3, 1929 to its intermediate-term high on November 11, the Dow Jones lost 50% of its value. October 23, 28, and 29 composed the majority of the 50% decline. President Herbert Hoover scrambled to meet with business leaders to come up with a plan to stop the panic. On December 5, 1929, Hoover met with 400 business leaders from the railways, banks, and manufacturing industries. He told the executives that three actions had been taken by the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve lowered its lending rate, refused to loan to banks who issued loans to stock speculators instead of businesses, and engaged in large-scale open market purchases of bonds, or quantitative easing. By May 1930, Hoover stated the depression was over. However, the economy and stock market crash was just beginning. In 1930, 26,355 businesses failed, and the country’s gross national product (GNP) dropped by 12.6%. In total, the GNP dropped 50% between 1929 and 1933. During the same period, automobile production dropped by 66% and residential construction dropped by 80%. Unemployment reached almost 20% with some cities such as Chicago and Detroit reaching nearly 50%. Bank failures were on the rise as well. Between 1929 and 1933, 43% commercial banks closed permanently. The largest commercial bank failure at the time was the Bank of the United States (not a government entity) on December 11, 1930 as 400,000 depositors lost a total of $300 million. From the stock market top of September 3, 1929 to its final bottom on July 8, 1932, the Dow Jones erased 90% of its entire value, resulting in one of the worst economic depressions the United States would ever experience. What started the decade at a roaring pace ended in crashing halt. The self-reflexive cycle of greed and fear fueled by excessive leverage had unfolded once again as per its usual boom and bust fashion.