In the early 1980s, the Soviet Union went through many attempts to make leadership changes until settling upon one person who would be a suitable candidate, Mikhail Gorbachev. Gorbachev believed that citizens’ voices and rights should not be suppressed nor should government have control over business. Workers in the Soviet Union worked but were never paid. Issues such as food shortages, long lines, corruption, and bribery plagued the country. Beginning in May 1989, Gorbachev aimed to carry out his reforms with the Law of Cooperatives which allowed private ownership of business. The government no longer would have control. Entrepreneurs were now able to open restaurants, shops, manufacturing plants, and would be able to start importing and exporting goods.

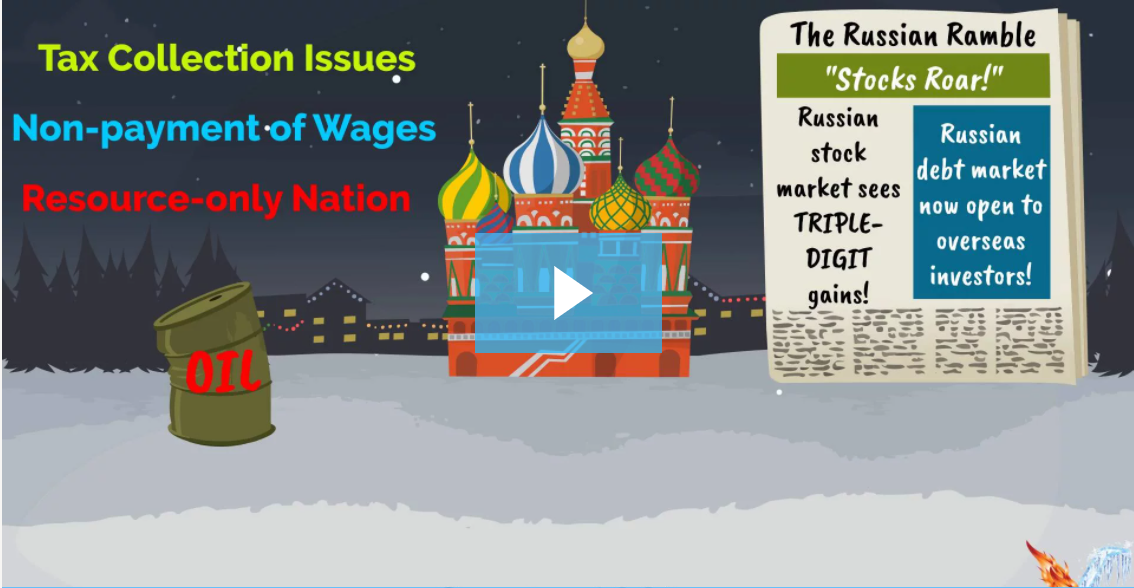

The Fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the rise of free speech and public opinion served as highly volatile events that shifted the economic course of the newly formed Russian republic. Although a minor accomplishment, in 1989, CNN was allowed to air its first ever unofficial news broadcast to guests staying at Moscow’s Savoy Hotel. Russians were allowed to watch an uncensored news broadcast for the first time in their lives. The amount of past Soviet debt the Russian republic was tasked with paying off reached over $60 billion by the time Russia became its own republic. However, during the 1990s Russia reiterated its commitment to paying its Soviet debtholders at the Paris Club. The inclusion in the Paris Club was a defining moment for Russia. Optimism increased and investors became excited. Russia opened its debt markets to overseas investors who were looking to buy Russian bonds. Although facing several underlying economic weaknesses, the Russian republic would experience a stock boom and bust.

The three underlying problems that sat idle during the boom, only to become relevant during the bust were tax collection, nonpayment of wages, and narrow revenue sources. As a new republic, the federal government was met with a fractured tax system. The federal government was not collecting taxes anywhere near what it was supposed to. Some reports indicated the federal government was only getting half the tax revenue. In an effort to combat potential corruption, local offices were set up to collect tax revenue instead of a central tax authority. Local offices were tasked with the collection of local taxes as well as the submission of federal taxes to Moscow. A widely used practice, however, would be for tax officials to work with local businesses to underreport revenues, lowering their federal tax bill, in exchange for extra payments to the local government. This would reduce tax expenses for local businesses and increase the tax revenue to local governments but would leave the federal government without enough tax revenue. This created a federal deficit. Nonpayment of wages in the public and private sector also became a major issue. This led to protest and civil unrest as most Russians could not buy what they needed to survive. Russia’s economy relied heavily on crude oil and metals as most of their country geographically could not produce perishables and other goods. This limited Russia to a narrow number of revenue sources. Despite these cracks in the economic foundation, Russia successfully reduced inflation from 131% in 1995, then to 22% in 1996, and down to 11% in 1997. As a result, overseas investors invested heavily into Russian stocks and bonds. The Russian stock market became the top-performing stock market in the world as the index saw triple-digit percentage gains. State short-term bonds called “GKO” were issued by the Russian government to investors. The interest on some of the GKO bonds were as high as triple-digits in the middle of 1997 which created an immense strain on the Russian federal government as they had trouble collecting tax revenue to pay the debtholders.

At the end of 1997, Russia’s export income started to decline as metal and oil prices began to plummet. President Yeltsin fired his current prime minister over corruption and appointed Sergei Kiriyenko as his replacement. The appointment of Kiriyenko was shocking to many as he was only 35 years old and had less than a year of experience in government. During the spring of 1998, a series of publicity blunders started to shake investor’s nerves. The chairman of the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) met with many high ranking officials and stated the government might be facing a debt crisis within several years if it did not make the necessary adjustments to increase the economy’s export income and decrease its expenses. Reporters in the room overheard the concerning comments by the CBR and news quickly spread the Russian economy was facing major troubles ahead. Another communication mishap occurred when Prime Minister Kiriyenko accidentally mentioned during an interview that the federal tax revenues were 26% beneath its goal and that the government was “quite poor now.” The third mistake occurred when Deputy Treasury of the Secretary Larry Summers visited Moscow to request a meeting with Prime Minister Kiriyenko. Kiriyenko’s aide, unfamiliar with Summers and suspicious of the importance of the meeting, denied Summer’s request. This series of communication blunders spooked investors and caused the Russian stock market to slump badly. Russian bond prices dropped considerably causing the interest rates on the bonds to soar as high as 47%. As the Russian ruble plummeted in value, the CBR took action to try and stabilize the currency. The steps the CBR took were the same as what the Bank of Japan carried out during the “Bubble-land Japan” episode and yielded a similar outcome. The CBR increased interest rates from 30% to 50% and bought billions of rubles with its dollar reserves. These actions created more pain as the ruble began to decline further in value. Businesses suffered as they could no longer afford loans being offered at 150%. Simultaneously, crude oil dropped to almost single-digits prices, never before seen in decades. This caused further strain on the Russian economy. Coal miners, fearful of not getting paid, went on strike and blocked the Trans-Siberian Railway. Russian workers were owed $12.5 billion in unpaid wages and poverty was becoming widespread.

As the ruble continued to decline, the CBR announced on September 2nd, 1998 that the ruble would float freely in the open market. Just a few weeks after the announcement, the ruble fell to an exchange rate of 21 rubles to $1, representing a further drop of 66%. Inflation began to settle back in topping at 84% in 1998. The purchasing power of the ruble weakened considerably. This caused imported goods such as cooking oil, sugar, and cleaning detergent to increase almost 4x the normal price. Alcoholism and drug abuse increased as deaths from alcohol consumption were cited at 35,000 per year compared to 300 in the US at the time. After weeks of worsening conditions, protestors crowded the streets. On October 7th, 1998 almost 100,000 people marched on the streets of Moscow with smaller demonstrations taking place in surrounding cities on the same day. Overseas investors who held Russian stocks and bonds felt the pain as prices began to decline considerably. The Russian stock market that had experienced substantial gains in 1996 and 1997, lost all of its gains in 1998. A high-profile hedge fund, Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), suffered massive losses from the Russian crisis. LTCM’s investment team was composed of Nobel laureates Myron Scholes and Robert Merton. On the fund’s launch date, the firm had $1 billion under management. LTCM traded mainly in Japanese, European and US bonds. The mathematical strategy yielded returns of 40% during the first few years of the fund’s inception. The fund’s size grew to $5 billion as a result of the initial winning trades. In early 1998, the fund positioned itself to take profit if Russian bonds held their creditworthiness compared to US bonds. If Russia experienced no economic trouble, the position would profit greatly. However, Russia experienced a whirlwind of economic problems and as a result, Russian bond prices tanked. The trade began to go against LTCM in May 1998, incurring a loss of 6%, then a loss of 10% by June. The hedge fund was so highly leveraged that on August 21, LTCM lost over half a billion dollars on the trade in just one day. Investors exited the fund in mass during the first few weeks of September causing the fund’s assets to drop from $2.3 billion to $400 million.

The Russian economy would eventually rebound as a bounce in energy prices in 1999 and 2000 would bolster Russia’s import revenue. The recovery in energy prices gave Russia the ability to restores its depleted reserves. However, Russia’s economy faced similar problems as the 2008 global recession rattled the Russian stock market once again. Volatility has no borders.