The Mississippi Company bubble is an important event to understand what would happen when a government attempts to constantly flood a weak economy with unlimited money. John Law would be considered by today’s economists as the world’s first Keynesian – someone who supports the idea that flooding an economy with government spending is the best way to address a weak economy. The word, millionaire, was even coined during Law’s Mississippi scheme as many people became millionaires from speculating on the price of the Mississippi Company. John Law was born from a family of bankers and goldsmiths, however he decided to use his knowledge of statistics and probabilities to become a professional gambler. He ventured throughout Europe to apply his gambling skills. He learned about the monetary and banking affairs of the countries he visited. In the early 1700s, the French economy was in shambles. King Louis XIV waged numerous wars that left France on the brink of financial collapse. The French national debt was about $3 billion and the wealth of the nation, mainly in the form of precious metals, was mostly spent. The currency of France in the 1700s was known as the livre tournois. The livre was equal to a pound of silver which was divided into 20 parts, then further divided into 12 parts. The shortage of precious metals meant there was not enough money in circulation. To apply a simple metaphor to describe the situation of the French economy; the French economy can be described as the body and the blood flowing within the body (gold and silver) was draining away. Law thought gold and silver was an outdated method of exchange. He proposed the idea that a wealth of a nation should depend on its ability to trade, not based on a fixed sum of gold. He thought paper money would serve as a better means of exchange between citizens than gold coins. He advised the French government to increase the amount of money in circulation by printing paper bills. At this time, France owned the Louisiana territory stretching up to Canada. Law’s plan to fix the French economy was to print an unlimited amount of paper bills and exploit the potential riches to be found in France’s Louisiana territory. Throughout his time in France, Law befriended the Duke of Orleans. The Duke became impressed at Law’s knowledge of monetary policy and recommended him to the Comptroller General of Finance after the death of King Louis XIV in 1715.

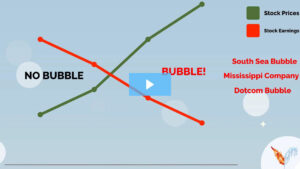

A royal edict was issued on May 5, 1716, granting Law the right to establish a bank. The bank was capitalized with ¼ precious metals and ¾ French bonds. 12,000 shares of the bank were issued to the public at a price of $500 per share. Law’s bank was granted exclusive trading rights with the Louisiana territory and created a company named “Company of the West” or “Mississippi Company” in August 1717. The price of the Mississippi Company was priced at $500 each and divided into 200,000 shares. Rumors began to spread that Louisiana was filled with vast deposits of precious metals. It was also rumored as a beautiful place where naïve natives would gladly exchange gold and silver for whatever knives, magnifying glasses, or other items the Europeans had to offer. At Law’s request, his company was granted a 25-year trading privilege with the Louisiana territory. In spite of the rosy and profitable image that began to emerge, shares of the company sank from $500 to $300. Law reassured investors that the company was fine and announced in six months the company would pay $500 for a certain number of shares. This would be the first time a company would make a promise to buy shares of their own company if it sank beneath a certain price level. This corporate action is known as a share buyback. Investors in the company saw this as a reason to hold their shares and further concluded the business prospects of the company were sound. As Law’s company began receiving more exclusive trading privileges in the East Indies, China, and South Seas, shareholder optimism grew with it. The price rose from $500 to $1,000 from May 1719 to August 1719. Major reasons for the stock price vaulting higher was due to the limited number of shares available, the use of margin via buying stock on a 12-month installment plan and share buybacks. In the fall of 1719, the price rocketed from $7,000, to $8,000, then to $9,000. The price soared, but so did the amount of paper money in circulation.

As the price rallied higher in the beginning of 1720, a few savvy traders began selling their shares of stock as they knew the mania would not last. They made trips to the Royal Bank to exchange their paper notes for gold coins. Some traders went to further lengths by depositing their gold in other countries in case the French government made possession of gold illegal. Law saw this as a potential warning sign his company would face a rush of sellers and made the Royal Court issue an order making payments of $100 in gold or silver and possession of $500 in gold illegal. The Royal Bank took measures to slow the withdrawal of gold from its vaults by put clerks in line who were simply there to lengthen the lines so others would not withdraw their gold that day.

The price of the company topped at $18,000 in August of 1720 and began its descent, crashing to below $8,000 in September 1720. As shares of the Mississippi Company began to fall from $10,000 to $4,000 in just a few weeks after September, Law made every attempt to try and calm investor’s emotions. John Law had 6,000 prisoners line up with shovels and axes bound for Louisiana that created the illusion that business was booming. However, this was merely a mirage. The prisoners lined up as if they were departing, only to leave when the crowd dissipated, sold their tools, and leave never to be seen again. As the price of the shares started to tumble, so did the French economy. Too much money was in circulation, causing the price of everything to rise considerably. The rising price of goods was at a raging pace of 23% per month. The calamity caused the Royal Court to become furious with John Law’s actions and stripped the Mississippi Company of its exclusive trading rights in November of 1720. The stock price sunk to below $2,000 in November 1720 and at the end of 1720, John Law was dismissed as the chief director of the bank. Ashamed and afraid, Law fled France disguised in woman’s clothing.

Law’s Mississippi Flaw reveals the ultimate fate of an economy that falls into a self-cannibalizing cycle of unlimited money printing, share buybacks, lack of corporate earnings, and the excessive use of leverage. Greed (ice) formed the bubble and as always, fear (fire) popped it. Volatility for the win.