The Myth

The biggest misconception retail investors believe is the right they assume when they buy a share of stock of a publicly-traded company. When retail investors were asked what they receive in return for their investment in a publicly-traded company, the most common answer was ownership in the company.[1] Not only is this answer incorrect, it begins to lead retail investors down a path of further assumptions that are also untrue, causing them to make investment decisions that lose money in the stock market.

Despite the general acceptance of the “ownership” assumption by economists and the finance community, the legal nature of a share of stock and shareholding is still uncertain.[2] Well-known corporate lawyer L.C.B. Gower touts a share does not fit into any normal legal category.[3] Corporate attorneys are clear what a share of a publicly-traded company is not, i.e., it is not an interest in the corporation’s assets.[4] A brief look at the history of stockholding will provide insight into this discussion.

Bondholding. The Beginning

Usury, otherwise known as loaning money for interest (a bond), was civilization’s first form of providing capital to businesses. The hostility towards lending money for interest can be traced to Biblical times.[5] Usury was frowned upon during Greek and Roman times and prohibited in the Middle Ages. The earning of interest on loans was later allowed but rates of return were regulated by statute. Aristotle said exchange was central to the social intercourse which made community, the pre-requisite of human happiness, possible. By providing a standard of commensurability for unlike things, money facilitated exchange and thereby made an important contribution to social bonding. Aristotle argued usury undermined money’s ability to perform these functions and subverted the fairness in exchange which was the salvation of states. Aristotle argued usury was unnatural, lacking genitals yet still able to reproduce itself. To Aristotle, usury was also unnatural in the sense that the acquisition of money tended towards infinity, endless multiplication, encouraging greed for its own sake.[6]

The Partnership

As trade grew during the Middle Ages and money became readily available to be borrowed and lent as capital, the negativity towards usury from religious institutions began to lessen and another form of investment was established through the creation of a “partnership.”[7] Shareholding via a partnership was seen as a more legitimate form of investment as there was a sharing of risk and venture of capital with no guarantees of getting the investment back as opposed to enjoying the benefits of usury with a contractual guarantee of return of principal. Most early partnerships were temporary, created for a specific trading purpose, then once achieved, ended upon assets being sold and proceeds distributed, enabling partners periodically to liquidate their investment and gain access to their capital.

The Birth of the Corporation

By the later 18th century, as industries grew, many partnerships started to become permanent, resulting in capital being tied up for prolonged periods of time. To gain access to their capital, investors had to destroy the business by selling off the company’s assets. For example, if a group of 4 investors wanted to build a canal to take advantage of a shorter distanced trade route and formed a partnership, they would have the following problems. If one of the investors wanted his or her money back due to hardship, an emergency or if a partner died and the inheriting partner didn’t want to be a part of the venture, it would be impossible to distribute his or her investment without having to sell off pieces of the canal, thus destroying much of its value. The canal is a “firm-specific” investment, meaning resources cannot be easily withdrawn without destroying at least part of the value of the investment.

The early-to-mid 19th century saw major changes in the economic nature of the corporation due to the rapid growth in the size and amount of public companies following the dramatic development of the railway system.[8] As a result, in the period after 1830, there emerged for the first time a developed market in a corporation’s shares.[9] Following the 1837 case of Bligh v Brent, shareholders had no direct interest, legal, or equity in the property owned by the company.[10] By 1860, the shares of both incorporated and unincorporated corporations had become established as legal objects and as forms of property independent of the assets of the corporation.[11] Returning to the four partners, if they formed a corporation, the canal or “firm-specific” investment would now belong to the corporate entity itself. The canal is now its own ‘person’[12] and can offer its shareholders limited personal liability, centralized management, indefinite legal life, and, in the case of public corporations, a liquid stock market where investors can sell their shares.

The creation of the corporation disallows any single investor from demanding back their share of the corporation’s assets. A board of directors is appointed to select executives to act on behalf of the corporate entity.[13] Shares of stock are issued to investors and a theoretical price is determined by market supply and demand. The shares of stock begin to trade in the expectations market, otherwise known as the stock market. How an investor receives his or her investment back is through selling shares of stock to another person at the current market price either for a loss or a profit. Expectations of how the company will perform over time are formulated into a visible share price so investors know how much they can exchange their shares for.[14]

The role of a shareholder is to provide capital. There is no guarantee the investor will receive his or her investment back in full or in part. When investors purchase a share of stock of a publicly-traded company, they do not receive any sort of ownership or interest in the company’s assets. They do not own a piece of the company.[15] Shareholders own rights when purchasing shares of stock. For buying a share of stock, the investor receives three rights – the right to vote, the right to sue, and the right to sell their shares. The rights to vote and sue have very limited ability in making directors and executives increase the share price and serve shareholder interests.[16]

In the 19th century, courts soon found it difficult to apply partnership law principles to lawsuits against corporations. For example, if a partnership was to be sued it was necessary to make all the partners party to the suit. Identifying four or five partners in a partnership is a simple task. However, discovering the identity of a public corporation’s shareholders, where the shares were freely transferable, was impossible.[17]

The courts developed a new tenet of modern corporate law, i.e., the legal personality of the corporation. A corporation is a fictional legal person, distinct from the actual people who compose it.[18] As determined by Salomon, the courts transitioned from partnership principles, which determined shareholders to be owners of the company, to the legal concept of treating a corporation as a separate person.[19]

The Roots of the Shareholder Ownership Myth

Because of the lack of any direct link between the share and the assets of a corporation, the term ‘share’ is a misnomer, as shareholders no longer own any property in common.[20] Principal-agency theory incorrectly attempted to explain the relationship between shareholders and corporations. The “Theory of the Firm” published in 1976 by business school dean William Meckling and finance economist Michael Jensen, attempted to describe the issues that arise when the owner of a business (the principal) hires someone else (the agent) to manage the day-to-day operations of the firm. Within the financial community, the relationship between shareholders and corporations defaulted to the idea that shareholders in the corporation played the role of principal while the executives were the agents.

The principal-agency theory states the following assumptions:[21]

1). Shareholders own corporations

2). Shareholders are the “residual claimants,” i.e., they receive all profits left over after the corporation’s contractual obligations to its creditors, employees, customers, and suppliers have been satisfied.

3). Shareholders are principals who hire executives to act as their agents

While the principal-agency theory model may describe a “firm,” particularly a sole proprietorship, or a closely held corporation with a single shareholder and no debt, it misstates the economic structure of a publicly-traded corporation. However, the principal-agency theory assumptions have not been supported by the following court cases.

The first assumption articulated by financial professionals, the media, and economists often asserts that shareholders “own” public corporations.[22] From a legal perspective, shareholders do not, and cannot, own corporations. Corporations are independent legal entities that own themselves, just as human beings own themselves.[23] Just as human beings can hold property in their names, bind themselves to perform contracts, and be held liable for committing torts, corporations are a “juridical person” and can do the same. Corporations own themselves and enter contracts with shareholders just as they contract with employees, debtholders, and suppliers.[24] According to Bligh v Brent, shareholders are beneficiaries of the corporation’s activities, but they do not have “dominion” over a piece of property.[25] The issue with treating shareholders as proprietors or owners is further invalidated by the absence of traditional feature of ownership: responsibility for the property owned and accountability, including legal liability, for injuries to third parties resulting from how business operations are performed. According to Salomon, shareholders cannot be held personally liable for the corporation’s debts or for corporate acts and omissions that result in injury to others.[26]

The second assumption of principal-agency theory is that shareholders are the only residual claimants. An analysis of bankruptcy court cases of publicly traded corporations performed by law professor Lynn LoPucki has determined that courts often require creditors to share in equity losses to some extent, i.e., that companies can have more than one “residual owner.”[27] The corporation owns the residual and it decides what it wants to do with it. If a corporation does well, the board of directors may declare a bigger dividend to pay shareholders, increase benefits to workers, offer scholarships to the community, or increase bonuses to directors. If a corporation does not do well, employees can be laid off, directors leave, and dividends may be reduced. Capital gains from holding a corporation’s shares are only realized if the shareholder sells their stock above what they paid for it.

The third assumption of principal-agency theory states shareholders are the principals who hire executives as their agents. According to agency law, a principal hires another person, an agent, to act in their best interest. The principal must come before the agent for this relationship to exist. However, when a corporation is formed, the first thing that occurs is that the firm’s “incorporator” must appoint a board of directors to act on the corporation’s behalf. After a board exists and a corporation is formed, only then stock can be issued to acquire shareholders. The corporation and its board of directors come before the shareholders, thus the idea of shareholders acting as principals hiring executives as their agents is invalid. Delaware is a legal home to more than half the Fortune 500 companies. According to developed Delaware corporate law, the right to manage the business and affairs of the corporation is held by a board of directors.[28][29]

Why It Matters

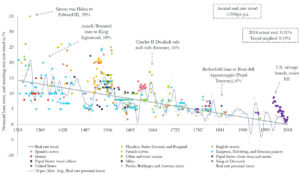

An investor having the mindset that his or her shareholding constitutes actual ownership of a corporation’s assets leads to short-termism, an obsession with quarterly earnings, and the constant valuation and re-evaluation of their shares. After all, investors believing they “own” a piece of a company by owning shares of their stock would not rest until they have come to a precise value of their shares. Tune into any financial media outlet and the obsession with short-termism and ‘quarterly capitalism’ becomes the norm amongst retail and even institutional investors.[30] To illustrate how short-termism has become the default investor mindset, the average holding period of public company shares by the average investor was 5.1 years in 1976, dropping to just 7.4 months in 2015.[31][32]

Financial analysts along with the investing public will try to determine whether the current market price of a stock is “undervalued” or “overvalued” by conducting an analysis using the company’s current financials. Unfortunately, predictions can only be made based on data that has already occurred and thus make no future indication of whether those earnings data will persist as such in the future. No matter how well the analysis is conducted, market prices can continue to divert from an analyst’s prediction for an unforeseeable amount of time. Additionally, accounting manipulation by management makes analyzing financial statements an increasingly difficult task. Economists debate that current market prices are fundamentally efficient, i.e., market prices already reflect all current and future expectations of a company.[33]

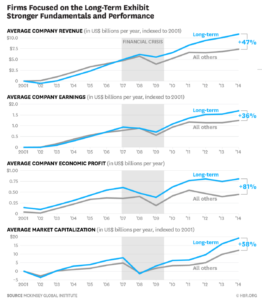

Companies that focus on short-term earnings maximization and increasing shareholder value make headlines more than companies who focus on long-term growth and the value of all stakeholders. However, it has been discovered that companies deliver superior results when executives pursue long-term value creation and resist pressure from analysts and shareholders to focus excessively on meeting Wall Street’s quarterly earnings expectations. Companies such as Unilever, AT&T, and Amazon succeed by sticking solely to a long-term view. New research led by a team from McKinsey Global Institute in conjunction with FCLT Global has found that companies that operate with a long-term mindset have consistently outperformed their industry peers since 2001 across almost every important financial measure. To identify long-term minded companies versus short-term companies, measures such as investment (ratio of investment to depreciation expense), earnings equality (underlying cash flow as opposed to accounting manipulation), margin growth, earnings growth, and quarterly targeting were used to filter through 615 large and midcap U.S. publicly listed companies. The long-term group consisted of 164 companies, about 27% of the entire sample. On average, the long-term oriented companies produced 47% more revenue, had 36% more earnings growth, took in 81% more economic profit, and grew 58% more in market capitalization than the short-term minded companies. Interestingly, companies that managed for the long-term added nearly 12,000 more jobs on average than their peers from 2001 to 2015. U.S. GDP over the past decade might have well grown by an additional $1 trillion if the entire economy had performed as the long-term group did from 2001 to 2015.[34]

Subnani Investment Research, LLC identifies and invests in long-term oriented companies for its clients and strives to maintain a long-term investment perspective. To signal their long-term perspective, Berkshire Hathaway uses the rolling five-year performance of the S&P 500 as its benchmark.[35] Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, GIC, publicly states it possesses a 20-year investment horizon.[36] The firm’s investment thesis is centered behind investing in management that serves the corporation’s best interest even though such actions may result in a depressed share price or unfavorable ratings from Wall Street analysts. Short-term underperformance should be tolerated and is expected if it helps achieve greater long-term returns. We believe investing in the long-term is statistically advantageous and welcome retail investors to become a client today.

References:

[1] Krupen & Subnani Investment Group, LLC 2019-2020 Investor Survey. 75% of the total poll answered, “Ownership in the company.”

[2] Ireland, Paddy. “Company Law and the Myth of Shareholder Ownership.” The Modern Law Review, vol. 62, no. 1, 1999, pp. 32–57. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1097073.

[3] Paul Davies, Gower’s Principles of Modern Company Law (London: Sweet & Maxwell, 6th ed 1997) 299, 321.

[4] Short Bros v Treasury Commissioners [1948] | KB 116.

[5] See Luke, 6:35 (mutuum date nihil inde sperantes, ‘lend, hoping for nothing thereby’); in the Old Testament, see Exodus, 22:25; Deuteronomy, 23:19; Ezekial, 18:17; 22:12; Nehemiah, 5:5.

[6] Aristotle, Politics I, 8-10; Nicomachean Ethics V. 5.

[7] John Noonan, The Scholastic Analysis of Usury (Cambridge Mass: Harvard UP, 1957) 133-134.

[8] Ireland, Paddy. “Company Law and the Myth of Shareholder Ownership.” The Modern Law Review, vol. 62, no. 1, 1999, pp. 32–57. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1097073.

[9] Rudolf Hilferding, Finance Capital (1909; London: RKP, 1981) 109-110; Paddy Ireland, Ian Grigg-Spall and Dave Kelly, ‘The Conceptual Foundations of Modern Company Law’ (1987) 14 JLS 149.

[10] Bligh V Brent (1837) 2 Y & C Ex 268.

[11] Paddy Ireland, ‘Capitalism Without Capitalist: The Joint Stock Company Share and the Emergence of the Modern Doctrine of Separate Corporate Personality’ (1996) 17 Journal of Legal History 40.

[12] Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd [1897] AC 22. “Salomon v Salomon – Case Summary.” LawTeacher.net. 11 2013. All Answers Ltd. 01 2020 <https://www.lawteacher.net/cases/salomon-v-salomon.php?vref=1>.

[13] Stout, Lynn A. The Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the Public. Berrett-Koehler, 2013.

[14] Roger Martin, Fixing the Game: Bubbles, Crashes, and What Capitalism Can Learn from the NFL (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press, 2011), 12-13.

[15] Bligh V Brent (1837) 2 Y & C Ex 268.

[16] Stout, Lynn A. The Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the Public. Berrett-Koehler, 2013.

[17] Paul Davies, Gower and Davies’ Principles of Modern Company Law 31 (6th edition, Sweet & Maxwell 1997).

[18] S Williston, History of the Law of Business Corporations before 1800 ‘2 Harvard Law Review.

[19] Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd [1897] AC 22. “Salomon v Salomon – Case Summary.” LawTeacher.net. 11 2013. All Answers Ltd. 01 2020 <https://www.lawteacher.net/cases/salomon-v-salomon.php?vref=1>.view 105, 106 (1888).

[20] Paul Davies, Gower and Davies’ Principles of Modern Company Law 31 (6th edition, Sweet & Maxwell 1997).

[21] Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure.” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 3, no. 4, Oct. 1976, pp. 305–360., https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0304405X7690026X.

[22] https://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/business/miltonfriedman1970.pdf

[23] Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd [1897] AC 22. “Salomon v Salomon – Case Summary.” LawTeacher.net. 11 2013. All Answers Ltd. 01 2020 <https://www.lawteacher.net/cases/salomon-v-salomon.php?vref=1>.

[24] Stout, Lynn A. The Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the Public. Berrett-Koehler, 2013.

[25] Bligh V Brent (1837) 2 Y & C Ex 268.

[26] Stout, Lynn A. The Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the Public. Berrett-Koehler, 2013.

[27] LoPucki, Lynn M., The Myth of the Residual Owner: An Empirical Study (April 29, 2003). UCLA School of Law, Law & Econ Research Paper No. 3-11. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=401160 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.401160

[28] Bower, Joseph L., and Lynn S. Paine. “The Error at the Heart of Corporate Leadership.” Harvard Business Review, Harvard Business Review, 1 May 2017, hbr.org/2017/05/managing-for-the-long-term.

[29] Delaware Code Title 8. Corporations § 141 Board of directors; powers; number, qualifications, terms and quorum; committees; classes of directors; nonstock corporations; reliance upon books; action without meeting; removal.

[30] Barton, Dominic, and Mark Wiseman. “Focusing Capital on the Long Term.” Harvard Business Review, 15 Aug. 2014, hbr.org/2014/01/focusing-capital-on-the-long-term.

[31] The World Bank, World Federation of Exchanges Database

[32] Bower, Joseph L., and Lynn S. Paine. “The Error at the Heart of Corporate Leadership.” Harvard Business Review, Harvard Business Review, 1 May 2017, hbr.org/2017/05/managing-for-the-long-term.

[33] Stout, Lynn A. The Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the Public. Berrett-Koehler, 2013.

[34] Barton, Dominic, et al. “Finally, Evidence That Managing for the Long Term Pays Off.” Harvard Business Review, Harvard Business Review, 9 Feb. 2017, hbr.org/2017/02/finally-proof-that-managing-for-the-long-term-pays-off.

[35] Barton, Dominic, and Mark Wiseman. “Focusing Capital on the Long Term.” Harvard Business Review, 15 Aug. 2014, hbr.org/2014/01/focusing-capital-on-the-long-term.