As economic turmoil shook the Russian, Japanese, and “Asian Tiger” economies of Southeast Asia during the 1990s, across the Pacific, another bubble began to form. The period of the 1990s is known as the Dotcom era to most Americans who were old enough to remember. The Internet has had its computer networks rooted before the 1990s. The first two nodes were connected in October 1969. The military and academia began plugging in to the systems throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In the early 1990s, the federal government changed the Internet from private to public use. The public internet allowed for a wider array of applications. Millennials and Gen Z’ers do not have a recollection of the events that unfolded during this period. However, if one understands the consistent 380+ year template of fear and greed emerging out of periods of great change or volatility, then living during the 1990s is not necessary to understand how the boom began and ended.

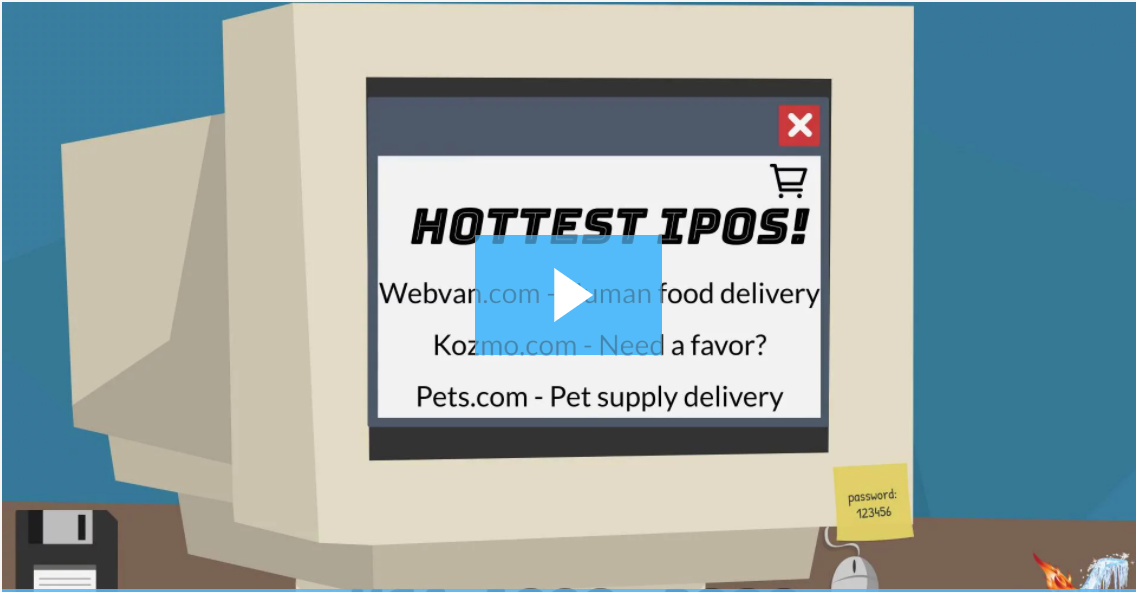

The beginning of buying things online and re-emergence of home delivery, a concept introduced in the 1920s, gathered immense investor interest. Consumers began buying or gathering information about almost anything online ranging from sports statistics, weather, stock message boards, stock quotes, stock charts, and stock trading to search engines, books, music, CDs, and computers. Almost every company that emerged during the dotcom scene was trying to figure out the most profitable way to connect the consumer to the Internet. As a result, the amount of companies that went public and had their stock listed on the NASDAQ exploded during the 1990s and reached over 500+ in 1996. When a company decides to have their shares listed for the public to purchase, the firm will undergo the “IPO” process. An IPO is an initial public offering in which the investment bank will value the company’s shares and offer the shares at a discount to the bank’s clients. Once the bank’s clients own the stock, the shares will be listed on an exchange, and debuted for public trading typically at a higher price. At this point, the bank’s clients can decide to sell their stock to other investors or hold it. Dotcom companies such as Pets, eToys, and WebVan delivered pet supplies, toys, and groceries to the consumer’s doorstep. Requesting someone to run a specific favor was just a click away on Kozmo.com. FreeMarkets, Webmethods, and Foundry share prices exploded 400%+ on the days the shares became publicly-traded. TheGlobe.com experienced one of the biggest first-day IPO pops of 606% when the stock began trading on November 13, 1998.

Bank analysts such as Henry Blodget were optimistic of the growth opportunities technology companies had. Blodget opined in an interview in early 1999 that “the stock market may very well be in a bubble but that this time it was different.” Many analysts such as Blodget thought this time it was different as well as the Dow Jones Industrial Average crossed 10,000 for the first time ever on March 29, 1999. Known floor-trader Ralph Acampora stated, “the 10,000 mark was now a floor and no longer a ceiling.” The optimism was at its peak as these emotions sounded eerily similar to 1929 Yale economist Irving Fisher’s comment which stated at the peak of the 1929 bubble that “stock prices have reached what looks like a high plateau and will not experience anything of a crash.” Books titled Dow 36,000 and The Roaring 2000s (projecting 41,000 in the Dow Jones by 2009 but was off by 80%) made bestseller lists. The euphoria was so rampant that author Charles Kadler wrote a book titled Dow 100,000: Fact or Fiction. The number of pages and advertisements in magazines related to stock trading grew exponentially. During Super Bowl XXXIV, television ads related to stock investing crowded the screen such as E*Trade’s 30 second, $2 million ad in which two men sat in a garage with a monkey clapping to music with an ending tagline that read, “We just wasted two million bucks, what are you doing with your money?” Magazines such as Fortune printed a cartoon of man angered, asking “why is everyone getting rich except me?” The public was pushed to partake in the stock mania by the media.

The main sources of fuel that sparked investor’s interest during the dotcom mania was the emergence of the CNBC finance news channel, a rise in retail trading, and a drastic cut in trading commissions from $100 per trade in the 1970s to $9.99 per trade in the 1990s. Schwab and Fidelity ushered in the first wave of online traders during the 1980s and other discount online brokers such as E*Trade and Datek brought in many more in the 1990s. Brokerage firms are the only winners in the game of online day-trading as commissions are charged regardless if a speculator makes money. Day-trading rooms began springing up all over the United States. As much as 60 different businesses with names such as Momentum Securities and All-Tech Investments Group were cheerleading the game of day-trading on. One report estimated there were as many as 6,000 full-time day traders during the dotcom mania. Despite the small amount, the day-traders accounted for up to 15% of the entire volume on the NASDAQ during the mania. Some individual stock’s daily volume was entirely dominated by day-traders.

Mismanagement of capital and overly rosy expectations caused major losses to many companies. Despite shares of theGlobe.com soaring 606% on its first day of trading, the company had revenues of $2.7 in the first nine months of 1998, but losses of $11.5 million. By this metric, the company was losing $4.25 for every $1 of revenue. Pets.com suffered a $300 million loss, eToys.com a $247 million loss, Kozmo.com a $280 million loss, and WebVan a massive $800 million loss. iVillage.com, a technology company with a website dedicated to astrology and relationships burned through $65 million of its funding, made a meager revenue of $15 million, and yielded a major loss of $43.7 million in 1998. The price-to-earnings ratio of the NASDAQ at its peak on March 13, 2000 was over 100, as opposed to 14 for normally priced markets. Savvy entrepreneur, Mark Cuban, was part of the speculative mania as Cuban cofounded Broadcast.com, an online radio company speaking on many topics ranging from sports, music, to TV. Cuban and the co-founders of Broadcast.com sold the company to Yahoo! Broadcast.com started trading at a $300 million market capitalization in the middle of 1998. This equated to 50x the revenues of the company. Yahoo! paid a fortune to Cuban and the founders of Broadcast. On April 1st, 1999 Yahoo! announced it would buy Broadcast.com for $5.9 billion, equating to a price tag of almost 275x the company’s revenue. After the sale, Cuban wisely profited from the fall of Yahoo! as he knew the company had overpaid and would sustain losses as a result. At the time Yahoo! was trading at an extremely high price-to-earnings ratio of 2,174 meaning an investor would be exchanging $2,174 of their dollars for $1 of Yahoo!’s earnings. Berkshire Hathaway, run by prominent investors Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, did not participate in the speculative mania. Toward the end of the late 1990s, Berkshire Hathaway’s performance lagged, however, Buffett and Munger would be right to sit out of the mania as the dotcom bubble eventually popped.

As the Federal Reserve slowly began inching up interest rates six times between late 1999 and early 2000, the NASDAQ finally topped on March 13, 2000 at 5,132.52. From its peak to its final bottom on October 9, 2002, the NASDAQ lost 80% of its value. From 2000 to 2002 technology companies accounted for a $5 trillion loss in shareholder wealth. There is an old saying that the media acts as the perfect contrarian in most cases. It isn’t often however that mass media points out a major turning point, but Barron’s would call close to what would be the top of the dotcom bubble on March 20, 2000. Barron’s posted a cover story labeled “Burning Up” and stated that “during the next 12 months, scores of highflying Internet upstarts will have used up all their cash.” The article was not sensationalist but based entirely on facts and company financials. This was a clear indication that a price bubble had formed and inevitably reached its final stage. Few companies would see a temporary bust yet emerge after and still exist as of 2020 such as Amazon, Google (now Alphabet), Priceline (now Booking.com), Adobe, Oracle, eBay, Yahoo!, IBM, and Microsoft. However, as the dotcom bubble ended in a typical crash, investors would not rest as the formation of the largest housing bubble would start in the following years. Volatility beats technology.